Even Here, Even Now

A sermon by Paul Peters Derry on Isaiah 9:2-7 and Luke 2:1-20

For a child has been born for us,

named Wonderful Counsellor, Mighty God,

Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace. (Is 9. 6-7)

May only Truth be spoken, and only Truth received. Amen

They’re called “chevrons” and for several years, for those of us who frequented travelling Highway 401 in the section east of Toronto, travelling “from the East,” from Oshawa through Pickering to Scarborough, white chevron pavement markings – horizontal arrows – introduced in the early-1990s as an educational program, reminding motorists not to "tailgate," always leaving a safe braking distance between us and the vehicle in front.

“The 401” – a highway with its number as its own proper name, like “the Permimeter” is a stretch of highway where, while there are speed limit signs, and at the time it was a limit of 100 km/hr. Most drivers treated those more as “speed suggestions” rather than “limits,” and most days, most times when the traffic was moving, it was easily at 120, 130 clicks, or more. Blue signs situated along the side highway advised drivers to “Keep 2 Chevrons Apart” and “Keep Your Distance.”

Over the years, these “chevron” pavement markings were removed through highway resurfacing, and not reinstated. Although the signs were taken down traces of the chevron pavement markings can still be seen on westbound sections of Hwy 401 that cross through Whitby.

That’s what you might call a “Fun Fact” for this year when this Advent 4 coincides with December 24th, meaning that Advent feels just a little bit shorter, and liturgically speaking at least, we find ourselves worship-in-the-fast-lane, Christmas Eve feeling as though it comes upon a midnight clear just that much sooner. That being so, we do well to position chevron-type markers between the two – Advent 4 and Christmas Eve – even as we rapidly transition, jumping into the Dr-Who-like telephone booth.

Even as it happens thanks to the quirkiness of this year’s calendar rhythm, so quickly, so unavoidably, the Advent season carries – or I should say, has carried – blue signs positioned along our spiritual thoroughfare, to “Keep Our Distance.”

Indeed, “Keeping our distance” has been, a sort of unofficial counter-cultural mantra for for us here at saint benedict’s table. As Beth so aptly preached on the first Sunday of Advent, we engage, we welcome and we proclaim the tension between the “already” and “not yet.” We keep our distance from the carols piped even throughout our spiritual-but-not-religious world, practically from late-October… or earlier. We testify to the promise, but we wait.

For me, this year, even as Advent has come rather truncated by the quirkiness of the calendar, the season started for me way back in September. Wednesday, September 13th, to be exact. That was the first day of the course I took through Vancouver School of Theology. Each Wednesday, from September 13th through December 13th, we gathered for a virtual seminar, “Creating Jesus: In Scholarship, In Film and In Fiction.”

The premise behind the course: ever since a babe born in the Bethlehem manger, there have continue to be, myriad attempts to put flesh on the bones of the incarnation. We can’t help ourselves. I believe that we shouldn’t even try. Indeed, a longing to incarnate the incarnation remains our undergirding urge.

In actuality, we glean precious little about Jesus from our Biblical record. Writers of the New Testament gospels were interested more in full-throttle good-news proclamation than anywhere-near-accurate historical documentation. Across the centuries, in many ways and by various means, historians, cinematographers and novelists have acknowledged the distance – the gaps and longings – and imagine what the life and experiences for Jesus might have been growing up. What was it like for Joseph, pulled off the bachelor bench, way past his best-before date? Or what was it like for Mary, a young girl who found herself to be “with child”?

Scholars, directors, artists and authors – then, as now – engage in such a quest in order to fill a vaccum, add colour and texture – all of that, and more than we could ask or imagine – and for an even more powerful, and simple reason:

We reach out to God, reflective of the essential tenet of our faith,

because, God, in the nativity of the Christ child, reaches out to us.

That forms the essential seed, or promise, of our faith stories.

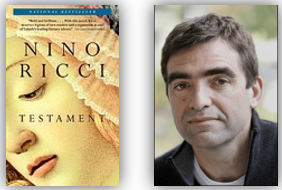

As part of the third Module for that “Creating Jesus” seminar, I had occasion to read Canadian author Nino Ricci’s novel, Testament, a collection of four “testimonies” or “gospel narratives,” imaginatively authored by 3 biblical characters, Yihuda of Qiryat (Judas), Miryam of Migdal (Mary Magdalene), Miryam (Mary, mother of Yeshua) and one imagined historical figure, Simon of Gergesa, a young Syrian shepherd who happened to be in Jerusalem during the Jesus’ final days.

Of particular interest as we gather on this most “Holy Night” when the chevron gap is erased is the gospel narrative Ricci imagines by Miryam (Mary, mother of Yeshua). In Ricci’s account, the story of Jesus’ birth is re-imagined with as a young, 15 yr-old girl, whose father had gained a place as clerk at the Court of Herod the Great. Miryam is the victim of some sort of coerced liaison involving a Roman legate. Whether or not this was arranged or even consensual between Miryam and the soldier, the legate “did not take me as his wife as my father had planned, but abandoned me the moment he had received his commission.” Effectively, Miryam is “married off” to Yehoceph, a mason employed at the temple works. All arranged by her father, a “rushed matrimonial celebration” takes place in Bet Lehem, and soon after, Miryam, Yehoceph and the babe escape to Alexandria. Yeshua, after all, has been born a mamzer – an Israelite of suspect parentage – a stigma with which he was forced to reckon, from the get-go, as were members of his immediate family.

Miryam … a young, Jewish girl, an innocent, helpless, vulnerable victim at the hands of a Roman soldier…. Preposterous? Incredulous? No less, and perhaps even a tad more acknowledgeable than the notions of a virgin birth, or for that matter, the suggestion that the Saviour of the World might originate from the backwoods, so-far-off-the-beaten-path hick-town of Bethlehem.

Not for even a millisecond endorsing of coercion, exploitation or abuse by one yielding power over another, what this angle on the story suggests – in point of fact not simply suggesting but boldly proclaiming – is that there is no gap, no chasm, no unfortunate, no way-past-impossible distance, that the Holy One will not envelope and encompass and incarnate.

In The Impossible Will Take a Little While, editor Paul Rogat Loeb, taking a phrase borrowed from Billie Holliday, Goska brings together fifty stories and essays that range across nations, eras, wars, and political movements.

· Danusha Goska, an Indiana activist living with paralyzing physical condition, writes about overcoming an individual and collective political immobilization.

· Vaclav Havel, former president of the Czech Republic, finds value in seemingly doomed or futile actions taken by oppressed peoples.

· Rosemarie Freeney Harding recalls music that sustained the Civil Rights movement.

· Paxus Calta-Star recounts the powerful vignette of an 18-year-old who launched the overthrow of Bulgaria's dictatorship.

Many of the essays are new, others classic works that continue to inspire. Together, writers explore a path of heartfelt community involvement that leads beyond or even through despair to compassion and hope.

The Impossible Will Take a Little While. Indeed it does. What we so boldly, tentatively but declaratively, unavoidably, ambiguously and yet at the same time, ever-so-clearly, proclaim this night: it has! We have, until now, kept our distance. Maybe even two chevrons apart. And yet, and even so, and long after the chevrons have been erased through wear-and-tear, let alone resurfacing and even re-pavement, disappeared through the unmistakable progress of history.

Through history and her story, that story of Miryam, mother of Jeshua, the distance has been bridged. Even here, even now. Even for always. Even unto the end of time.

So they went with haste and found Mary and Joseph, and the child lying in the manger.

When they saw this, they made known what had been told them about this child;

and all who heard it were amazed at what the shepherds told them.

But Mary treasured all these words and pondered them in her heart.

The shepherds returned, glorifying and praising God for all they had heard and seen, as it had been told them. (Lk 2. 16-20)

+ In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. Amen