Clark Kent Does Not Exist

- a reflection by Davis Plett

This is a story about an old man. It is also a story about Clark Kent.

In the university I attend, at the top of the fourth flight of stairs, beside the fourth floor lecture room, there is a door. There is never a light on inside. I know this because there are slats in the door and the spaces between the slats are always dark. There is no sign on the door to say who the room belongs to.

In my second term I had a philosophy class every Thursday afternoon on the fourth floor around the corner from the blank door. Always it was locked, its maw zipped shut, keeping quiet. It was a door that was meant to be forgotten.

Then, one day, it opened. I came up the stairs and it was unlocked, gaping, ready to speak to anyone who would stop and investigate. I could see books—piles of books on pantry-like shelving, and large rolls of paper—maybe maps—strewn like children’s toys on the floor. More importantly, standing with his back to me in front of the glorified closet, there was a man without a head. I know only one person who doesn't have a head.

“Dr. Gold!”

The man who pivots towards me has a face that has seen better days but doesn't seem to know it. He grins like he has just made an astounding discovery and his eyes are huge, which is mostly because the glasses that cover half of his face are as thick as windows. The reason he doesn't have a head but still has a face is that his back is hunched; if you see him from behind, at just the right angle, it looks like some enterprising Roman soldier has chopped off his fine old Anglo-Saxon cranium, foamy-cornered grin, magnifying glasses and all. He must have some kind of degenerative spinal disease, although I have my own theories about this.

He was a classics professor. I really ought to say that he is a classic professor because, although he has been forced into an honourable academic retirement, he has never stopped teaching. I first heard him speak—on the architectural marvels of the Roman arch of all things—at a library where he was giving a free lunch hour lecture when I was about twelve years old. My enterprising homeschooling mother asked him after the lecture if he would come speak to one of our homeschooling groups. He agreed.

Our group met in a church. Every other Friday we would cram ourselves into a side room, where the heat never worked, and a couple of us would help Dr. Gold set up his slide-projector. He had taken almost all the slides himself, on his trips to Athens, to Mycenae, to Rome, in the days before his wife became too sick to travel. He would talk for several hours at a time, illustrating the wonders of Greek pottery, the marvels of Roman jewellery, the history of the Phoenician alphabet. Occasionally he would sober at a serious part of a story before once again bursting into grins and guffaws. When he finished giving the lecture on arches (it was clearly a long-standing part of his repertoire), everyone clapped, like we’d been to hear an especially good concert. I remember six-year-olds clapping.

Dr. Gold is flying now, an old man off his rocker, dancing an academic jig in the middle of the hallway on the fourth floor. Students squeeze by us; we are blocking the flow. He tells me about the lecture he gave that morning to a group of seniors. I believe he said the lecture was three hours long. If I hadn't had a philosophy class to get to, I am sure he would have given it all over again, spinning out tales of far-off times, of ancient graffiti and palace frescoes and archaeologist questers.

Before I go, he tells me the story of how he came to be the keeper of the unmarked room. When he “retired,” the university, presumably realizing that they could give him a pension but could never make him quiet, had given him this tiny room as a sort of on-campus office that you couldn't work in. I’m not sure that there even was a light in there.

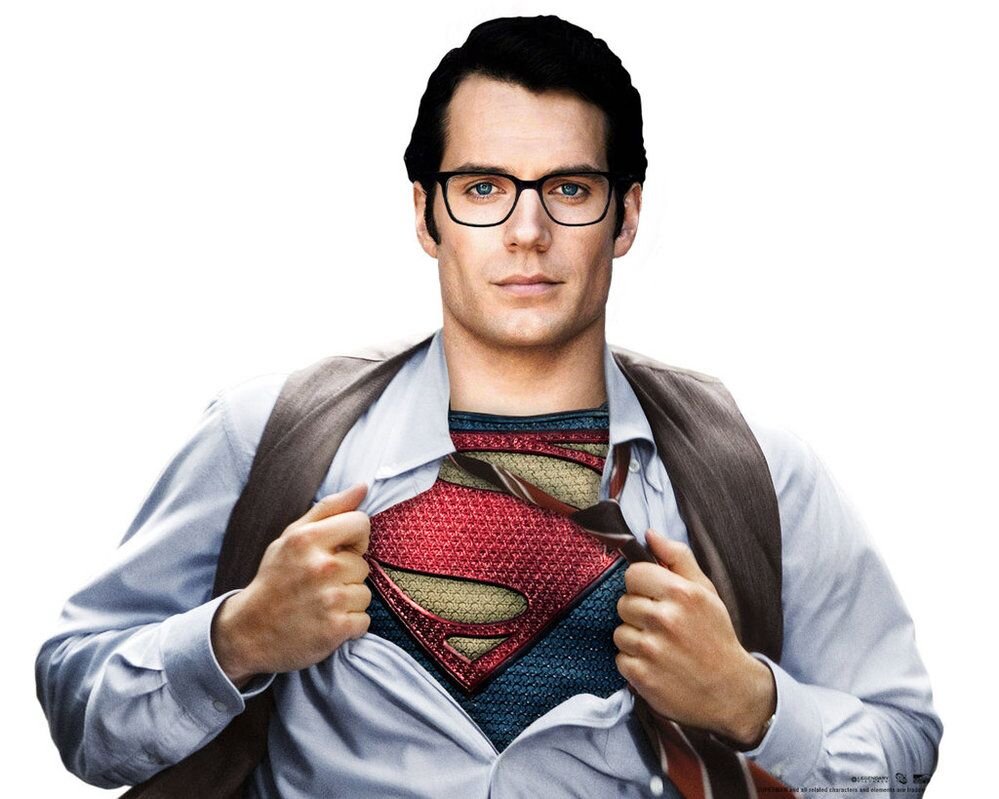

Beaming like a maniac and bouncing his hands for emphasis, he says, “When I told my wife about this telephone booth of an office, she said, ‘Yes, you and Clark Kent!’ Ha, ha, ha!”

Dr. Gold, Dr. Clark Kent, Dr. Burning Bush Gold, why didn't they give you a name? Where is the marble plaque for your office door? Why isn't this entire establishment built around the love and light that bounce around inside your brain and get magnified into a dusty light show when they shine through your silly glasses? Why don’t all the institutional gears fall silent before what comes out of your head, your head that is bowed down because it holds libraries—Babylon, Alexandria, Congress! —and, maybe, I don’t know for sure, because you sing in your church choir? Where are the crowds, the reporters, the film crews to gasp at your emergence from that pregnant darkness in the broom closet? Anyone would think that little closet of yours belonged to a janitor.

Ah, of course, that is the answer to these questions. The janitors don’t have names either. They work when the rest of the world is sleeping, opening their unmarked doors, digging up Pine-Sol bottles and stained sponges from dark closet interiors so they can scrub permanent marker obscenities from bathroom walls. I defy anyone to say that they aren't worthy of a name on their doors.

Dear old Dr. Gold. I had to go. I had a philosophy class to get to. We talk about Clark Kent in philosophy class too, oddly enough, but only as a theoretical entity, a useful analogy for some philosophical problem that I don’t remember. It’s not like he’s real.