For the Time Being | an Advent sermon

An Advent sermon by Jamie Howison

CHORUS

Joseph, you have heard

What Mary says occurred;

Yes, it may be so.

Is it likely? No.

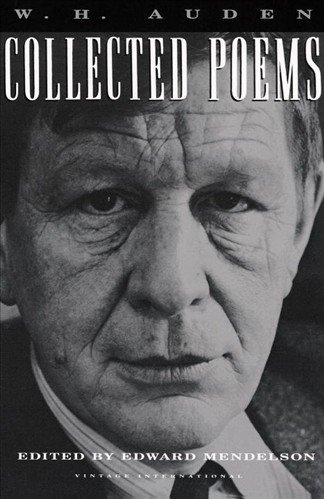

Those are lines from W.H. Auden’s long poem, For the Time Being: a Christmas Oratorio. In the edition I own, the poem runs fully fifty pages divided into nine sections, stretching from the first one—Advent—through to the final one—The Flight into Egypt. It is at times an extraordinarily complex poem, with multiple voices—Gabriel, Mary, Joseph, shepherds, Magi, soldiers, Simeon, and so forth—punctuated with what Auden called his “choruses” voicing other concerns, ideas, and emotions. At times it is almost too dense for the reader to disentangle… and then there are these sections that are so crystal clear that they are riveting.

This section—The Temptation of St. Joseph—is one of those. Auden wrote this poem during the Second World War, and when we come to the figure of Joseph the setting is very clearly a London pub during the war.

“My shoes were shined, my pants were cleaned and pressed,” this section begins, as Joseph rushes off to meet his beloved in that pub. But once there, he’s not so sure. Will she come? Is the gossip on the street perhaps true? Has my beloved been with another man?

When I asked for the time,

Everyone was very kind.

CHORUS

Mary may be pure,

But, Joseph, are you sure?

How is one to tell?

Suppose, for instance… Well…

Well… well what? Auden’s Joseph is somewhere between heartbroken and lost, sitting there in that pub and wondering what in heaven’s name has happened to Mary… to him. The chorus again:

CHORUS

Maybe, maybe not.

But, Joseph, you know what

Your world, of course, will say

About you anyway.

And then comes a long prayer—a plea, really—now set in rooms in the house where he has been staying. The feel is that of a long, cold, lonely night.

Where are you, Father, where?

Caught in the jealous trap

Of an empty house I hear

As I sit alone in the dark

Everything, everything,

The drip of the bathroom tap,

The creak of the sofa spring,

The wind in the air-shaft, all

Making the same remark

Stupidly, stupidly,

Over and over again.

Father, what have I done?

Answer me, Father, how

Can I answer the tackless wall

Or the pompous furniture now?

Answer them…

And now it is to the angel Gabriel, who speaks to Joseph in that dark lonely place.

“No, you must,” Gabriel says. Let me read to you the exchange between Joseph and Gabriel:

GABRIEL

No, you must

JOSEPH

How then am I to know,

Father, that you are just?

Give me one reason.

GABRIEL

No.

JOSEPH

All I ask is one

Important and elegant proof

That what my Love had done

Was really at your will

And your will is love.

GABRIEL

No, you must believe;

Be silent, and sit still.

Matthew’s telling of the story is brief. “Mary’s betrothed husband Joseph, being a righteous man and unwilling to expose her to public disgrace, planned to dismiss her quietly. But just when he had resolved to do this, an angel of the Lord appeared to him in a dream…” A message is conveyed to Joseph in that dream, and he accepts it. “When Joseph awoke from sleep, he did as the angel of the Lord commanded him.” Just a few lines, and aside from a few brief appearances in both Matthew and Luke, it is all we see of him.

What Auden has done is to explore the textures of the man, offering a picture of someone who will trust, yet for whom that trust doesn’t at first come easily. The novelist and essayist Reynolds Price has called such treatments as Auden’s “A Serious Way of Wondering,” writing that “I knew that the act of telling a story, especially a story invented as one tells it, can sometimes become a moral discovery or (as any child knows) a private vision that approaches revelation in intensity and personal usefulness.” (Price, A Serious Way of Wondering)

This is, I believe, what Auden offers to us on this night, when we tell Matthew’s brief account of Joseph’s discovery that his beloved Mary is pregnant. We are reminded that there is a real, historical character behind Matthew’s story, and one who would have felt precisely the sorts of things any one of us here might have felt. Yes, he’s described as “a righteous man” by Matthew, but that does not mean that Joseph wouldn’t have had to wrestle with the very human and very emotional situation into which he had found himself cast.

That is enormously important for we who read these stories some 2000 years after the gospel writers first set them down. Yes, they were most clearly interested in showing us Jesus, but seeing all of the other figures in their full humanity is critically important. We are human and made in the image of God, just as they were. We also can limp along with our scars and wounds, our questions and doubts, just as did Joseph and later Peter and the whole host of characters. Yes, in the annunciation story young Mary replies to Gabriel with a stunningly innocent and trusting “let it be with me according to your word,” but there are other moments along the way where we see, even in her, the scars of disbelief. Recall the day she and her sons tried to rescue Jesus from the crowds, wondering if he’d lost his mind (Mark 3:21-35). But maybe I’d be afraid of precisely the same thing, were I Mary or one of those brothers.

Resist the temptation to read and hear these stories from a safe arm’s length, and dare to enter them seeing the very human textures that are born by all of those people.

And this night, with the help of W.H. Auden, remember what Joseph was prepared to set aside in order to be faithful to both his God and his betrothed. And ultimately to the infant and child Jesus, for whom he filled the roll of a father; of a dad.

Let these stories sing with truth, with very human textures, even with grit. When we do that, they have the potential to transform our very hearts.

“No,” Gabriel said.

No, you must believe;

Be silent, and sit still.